Have you ever wandered through a traditional Pahadi village? Beyond the

breathtaking landscapes, what captivates the senses are the village houses

constructed with a harmonious blend of wood and stones, topped with roofs made of

slate.

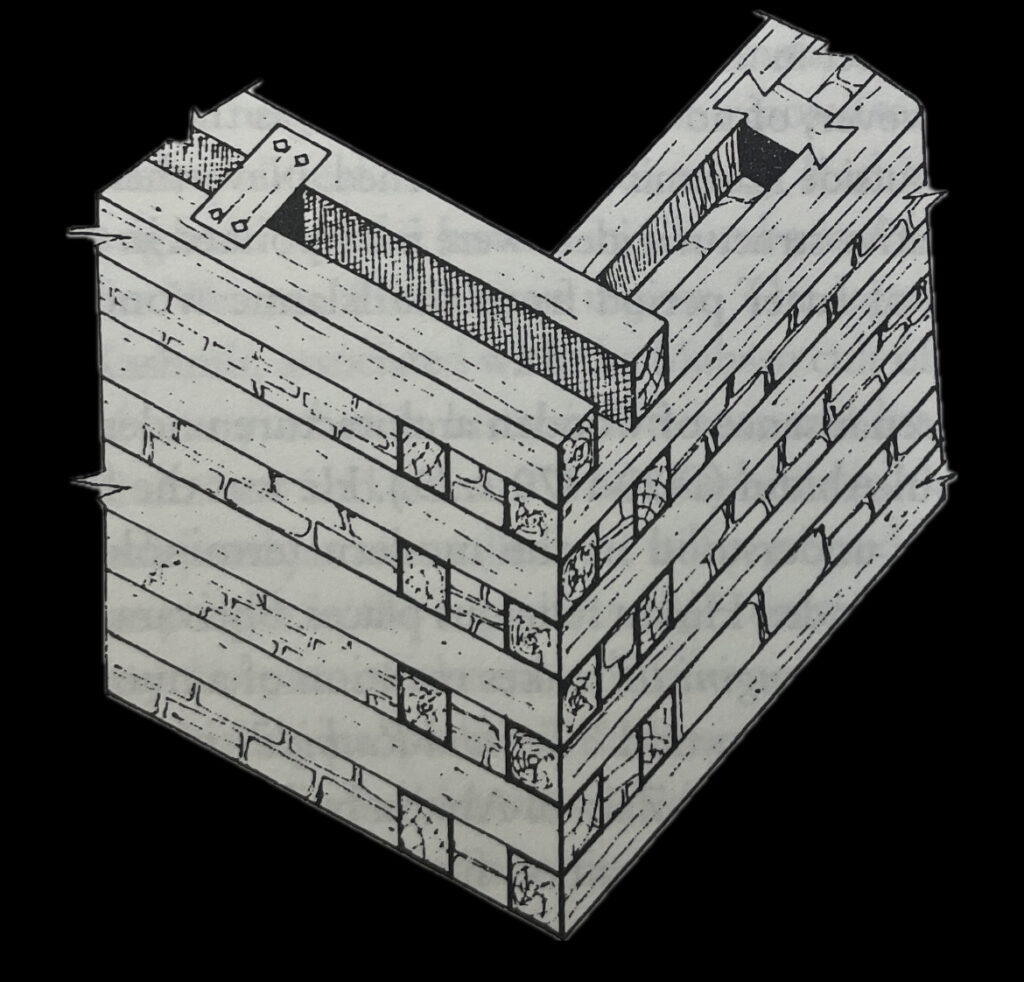

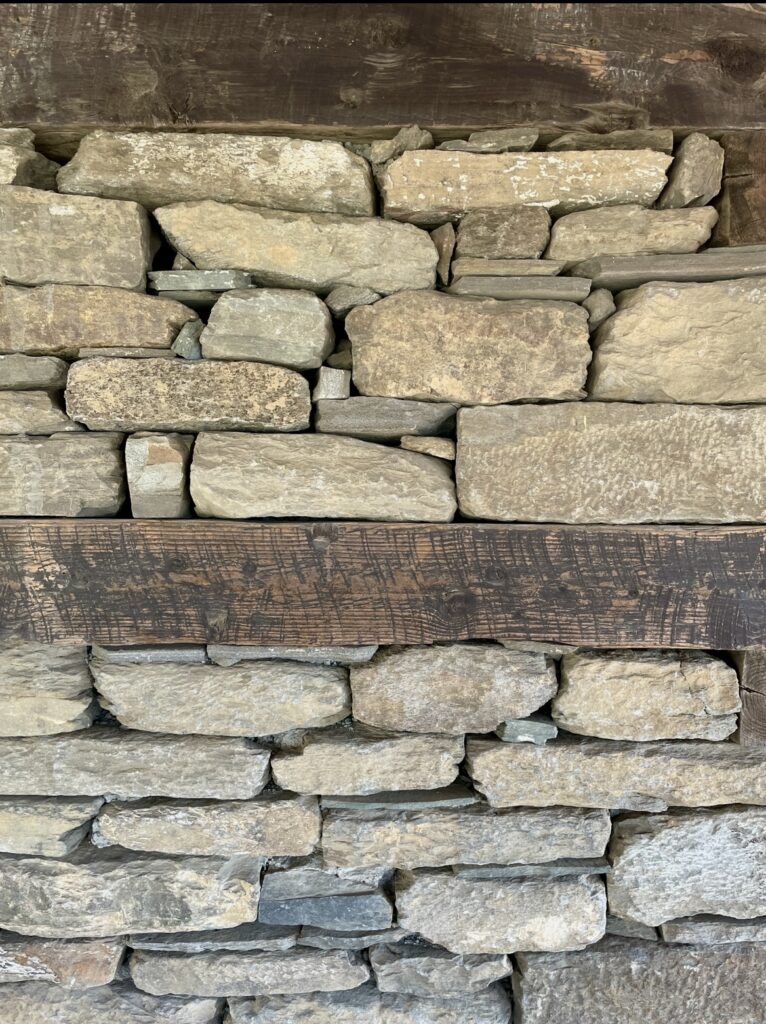

This architectural legacy, prevalent throughout the Himalayas, especially in Himachal

Pradesh, is known as kath-kunni. “Kath” is derived from the word ‘kasth,’ meaning

wood, while “Kunni” signifies the corner. Essentially, kath-kunni is a unique wall

construction technique where stones are meticulously placed between wooden

beams, and corners are fashioned using wood, adapting to the needs of the

occupants.

Crafting a kath-kunni structure demands expertise in selecting suitable wood, stone,

craftsmanship, and an understanding of local conditions. Local artisans, referred to

as “mistri,” inherit this knowledge from their ancestors. Notably, strict spiritual rules

are adhered to during construction, particularly for temples, and these rules may vary

across regions.

The high hills of Himachal provide an abundance of wood and stones, making kath-

kunni structures a sustainable solution. The wood primarily used is from the Deodar

tree, known as the ‘Devdar’ or the tree of Gods. With its straight veins and

impressive durability, Deodar wood is utilized in various structural applications. A

popular saying attributes an exceptional lifespan to this Himalayan wood, lasting up

to 1,000 years in water and significantly longer in air, with fire being its primary

adversary.

The design of a kath-kunni structure exhibits various forms. Typically, a Pahadi

house comprises two to three stories, with the ground floor often designated for

cattle.

A remarkable example of Pahadi construction can be witnessed in Chehni

Village, boasting the tallest kath-kunni structure in the entire Western Himalayas.

Despite the challenges of constructing tall structures with stone, the local craftsmen

at Chehni have meticulously arranged the stones, and the structure endures even

amidst harsh climatic conditions.

Situated in a high seismic zone with extreme weather conditions, the kath-kunni

structure serves as a solution to both challenges. The thick walls made of stone and

wood, coated with mud, act as effective insulation against severe winters. The

interlocked wooden beams within the walls provide remarkable ductility, allowing the

structure to adjust during earthquakes, dissipating seismic forces without breaking

apart. The use of slate tiles for the roof adds weight, enhancing stability.

4 thoughts on “Unraveling the Craftsmanship of Kath-Kunni – A Timeless Building Legacy”

I’m extremely inspired together with your writing skills and also with the layout to your weblog. Is that this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it is rare to look a nice weblog like this one these days!

Thank you for your thoughtful and bold writing.

I want to use one of your photo in my writing about cost effective and environment friendly building construction technology.

Thanking You again in advance for your permission. Definitely I will mention source of photo is himflavours.

Hello Jaydip ji. Thankyou for the kind words. We would appreciate if you mention the website as a source from where you took the picture. Please share your piece of writing with us as well.

It is really a great and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.